Deepening Students’ Vocabulary and Fascination with Words – Key Practices

Reading time

Date posted

By Mary Ehrenworth, author of Vocabulary Connections

When I was a new classroom teacher, captivated by the precocious language that many of my readers produced, I thought that reading itself would build my student’s vocabulary. My students would glean words like malicious and malevolent from Lemony Snicket and Roald Dahl and Christopher Paul Curtis. I was partially right about this process, which is known as incidental learning. Linguist Elfrieda Hiebert describes how texts are a source of vocabulary acquisition (2020). Cunningham, Burkins, and Yates similarly allude to how reading enriches language (2023, 80). Any teacher who listens to a five year old explain the difference between a Velociraptor and a Tyrannosaurus Rex, knows that, when children fall in love with a topic, they can develop startlingly expert vocabulary. Chances are also strong that when we listen to a young student express themselves with glimmering vocabulary, we’re probably listening to an avid reader.

I was wrong, though, in not taking a more direct approach to vocabulary instruction. It’s too important for all our students that they develop literary and academic vocabulary, and that they become conscious of how words work. These are neither skills nor knowledge we can leave for students to infer from their reading. There are equity issues involved in democratizing vocabulary acquisition, especially as it is correlated with reading comprehension (Cabell, 2020; Duke & Pearson, 2021). Fortunately, it’s not hard to weave direct vocabulary instruction into existing classroom structures.

In Vocabulary Connections: A Structured Approach to Deepening Students’ Expressive and Academic Language (2025), I share classroom practices, protocols, and lessons that teachers can implement inside of and alongside their literacy curriculum. In the book, I focus on literary vocabulary, domain vocabulary, and word consciousness (etymology and morphology). Here, in anticipation of May-June being a great time for innovation, piloting, and planning, I’ll share two ways to organize your approach to vocabulary that cross these categories, ones that you can dive into immediately, and that you can easily incorporate into your planning for the fall as well.

Collect Vocabulary in Context

In vocabulary acquisition, context is everything. When students learn vocabulary in the midst of learning about something they find fascinating, they attach lasting, contextual meaning to words (Ehrenworth, 2025; Hiebert, 2020). Developing vocabulary collections as students learn new content leads to deep contextual understanding, rather than fugitive memorization.

For literary vocabulary, high-leverage words to collect are words we use to describe characters. If you read aloud My Papi Has a Motorcycle, for instance, written by Isabel Quintero and illustrated by Zeke Peña, and invite students to collect words to describe Daisy, they’ll soon have a collection of words like curious, independent, passionate, loving, affectionate, adventurous. As you pick up the next story to read aloud, or as students pick up their own books, you can immediately ask, ‘is the character in your story like Daisy? Are they curious and independent?’ That Tier 2, specific vocabulary (Beck et al., 2013), becomes meaningful not because it was on a vocabulary list, but because readers associate it with Daisy.

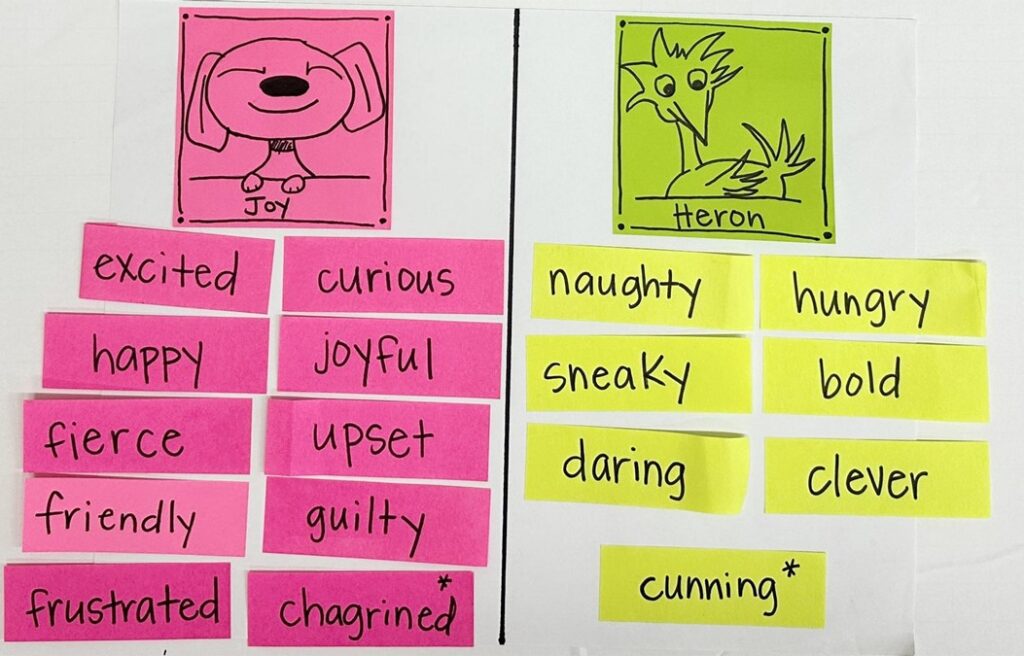

I like to start by ‘reading’ a digital narrative – a wordless video – together, like Pixar’s Joy and Heron, and collecting words to describe the characters. As readers collect and talk about these words, they are really developing more nuanced ideas about the characters. They also learn to read closely, attending to detail.

To watch a video of me teaching literary vocabulary collection, visit https://www.vocabularyconnections.org/videos .

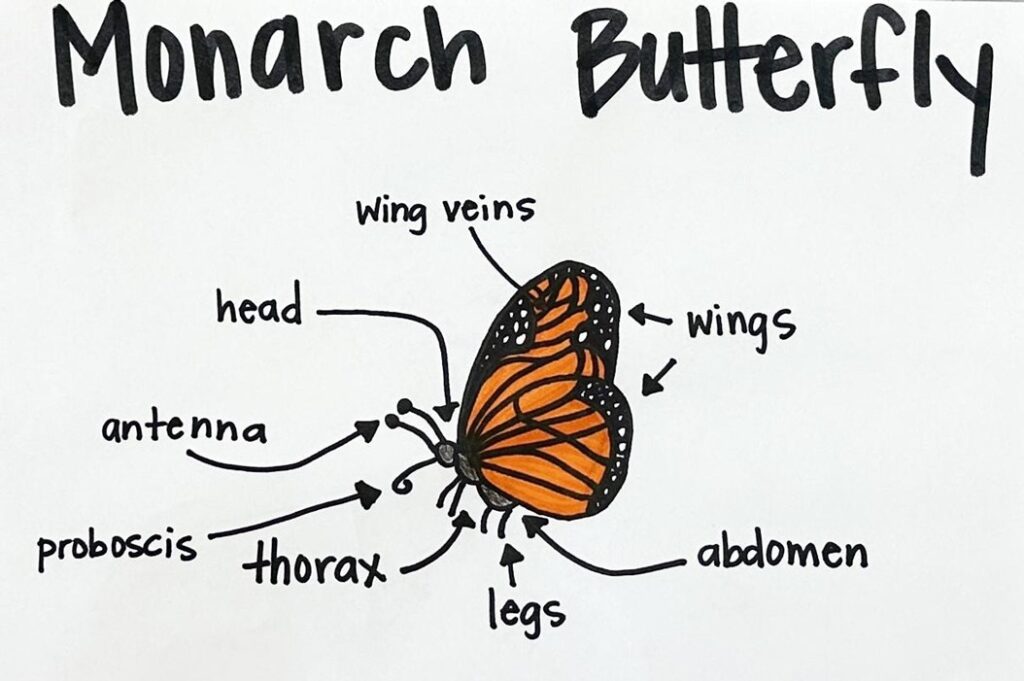

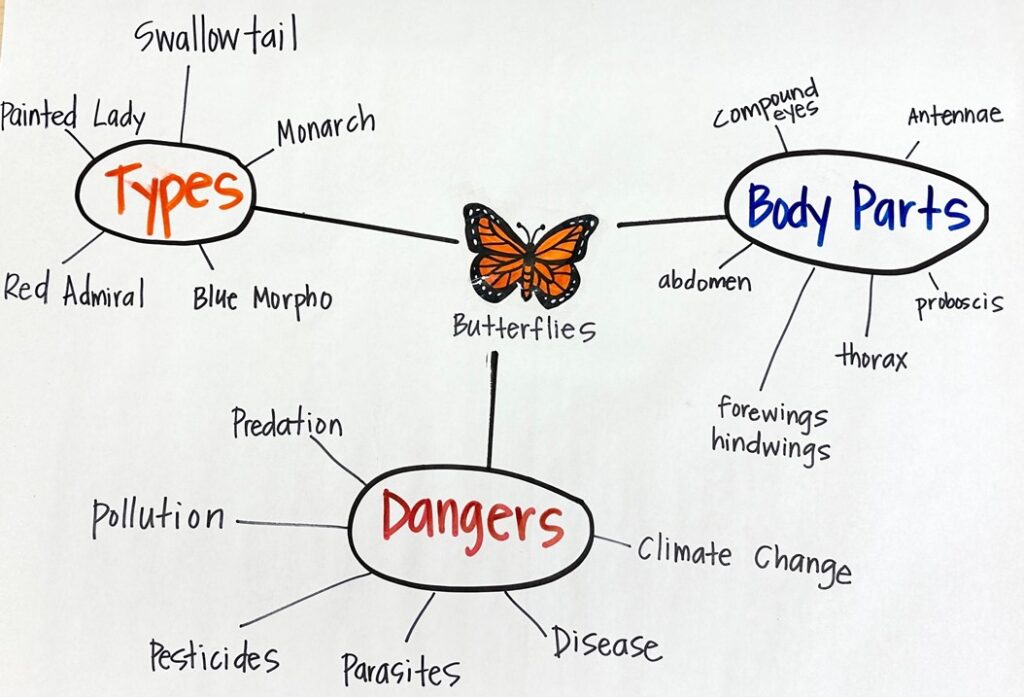

Collect domain vocabulary as well, whenever students are studying content. If your students are studying insects, they’ll soon have a collection of words that include expert vocabulary like exoskeleton, antennae, chrysalis. They should include words that are important and specific in the context of this topic. For instance, students will probably know the word pond, but can they explain why ponds matter to dragonflies? As students explain their significance, they are developing historical or scientific explanations. Sketching and labeling is a first step in noting domain vocabulary. Then students can add captions to their notes, and collect envelopes of domain vocabulary that they can use as a starting point for conceptual sorts, discussions, and writing projects.

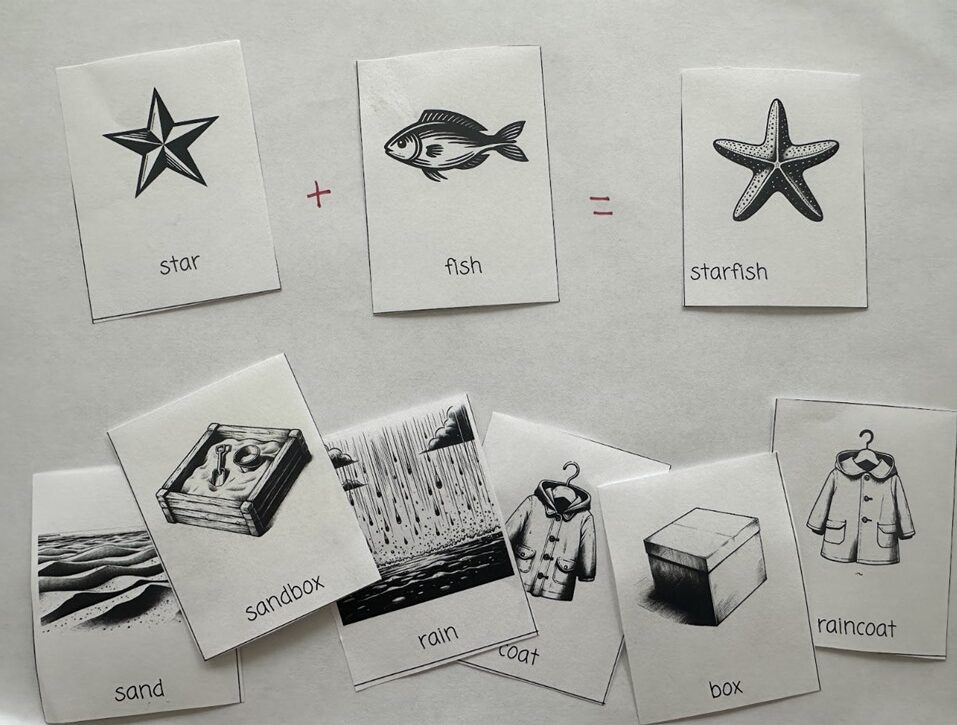

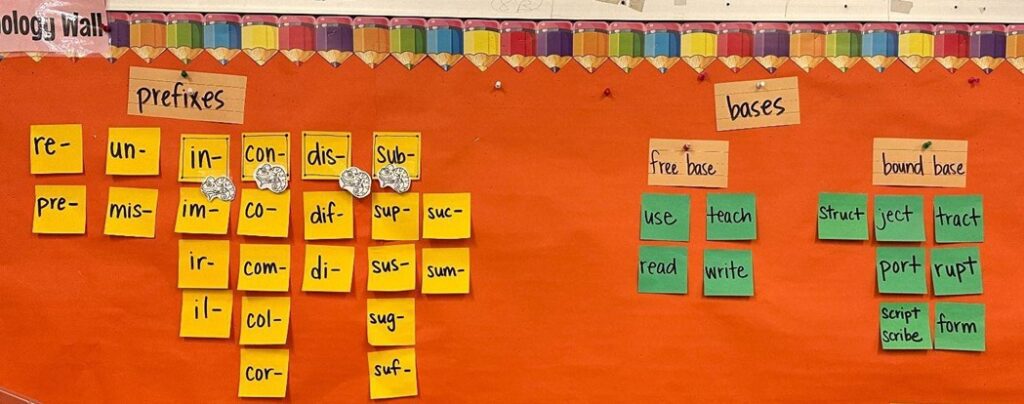

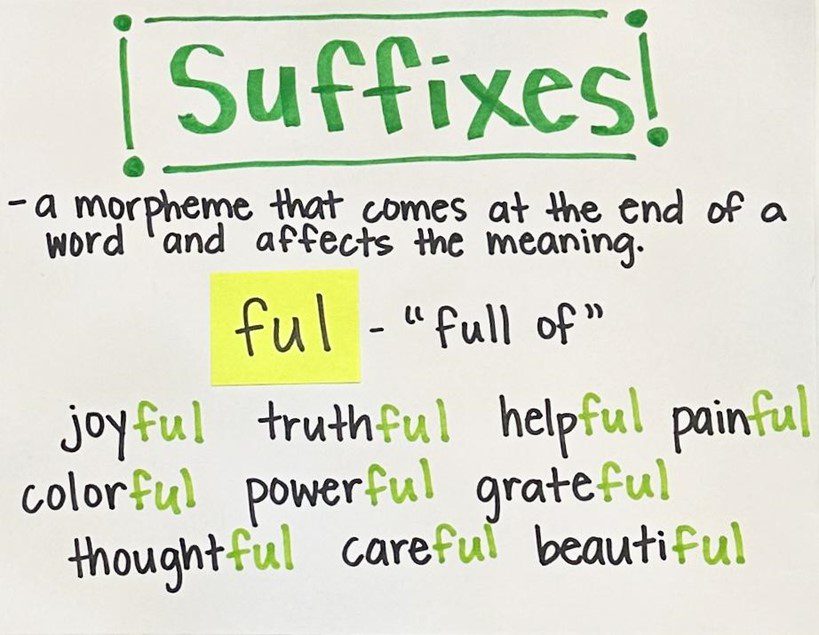

In a similar way, you can develop collections of word parts as you teach etymology and morphology. Whether you are studying compound words, cognates, or morphemes, grouping words – and parts of words – by meaning, makes it more likely that students develop transferable, contextual understanding that helps them apply their knowledge when they encounter new words.

Organize Word Walls as Semantic Clusters

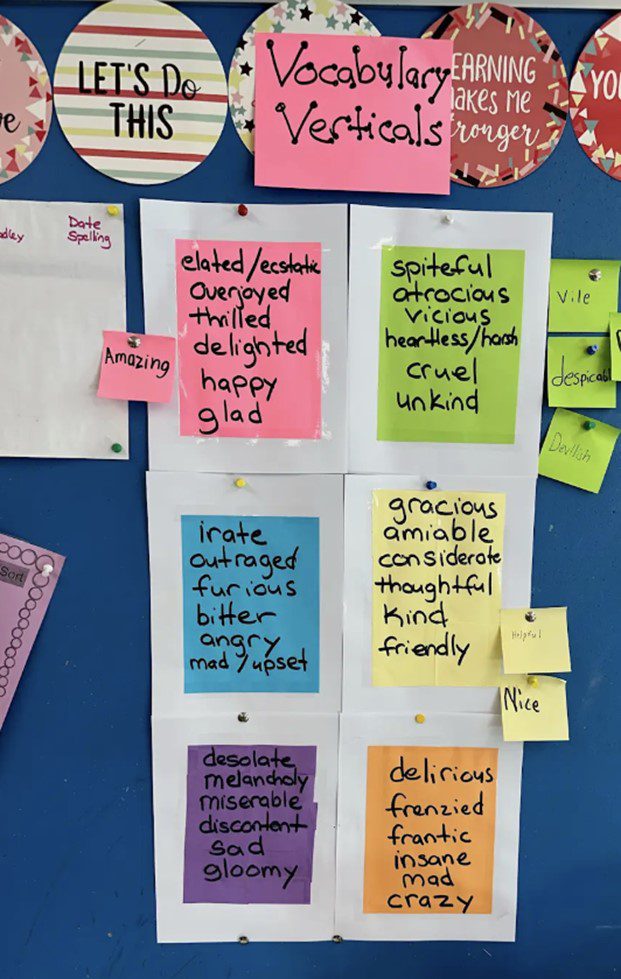

Once you and your students begin to collect vocabulary in context, you’re ready to re-imagine your word walls as semantic clusters – words that are grouped by meaning (Ehrenworth, 2025; Hiebert, 2011, 2020). Here are some examples of classroom word walls that cluster words by meaning.

Verticals

Words that are grouped and arranged by shades of meaning become high-leverage tools for developing more nuanced literary vocabulary and literary conversations. Conversations sound like, “at this moment, do you think the character is a little mad, like annoyed, or incredibly mad, like furious?” Verticals are helpful when displayed on the wall, because you can turn to them while reading aloud, and also helpful in students’ hands, so they can use them during book club conversations. Often it helps to offer starter vertical sets, which kids can add to.

Diagrams and Semantic Maps

Sort and display content vocabulary in a way that reinforces relationships and categories. I’ve seen teachers put words on magnets, so students can rearrange them in different groupings; you might choose to give students whiteboard markers to use on desks or use large sticky notes as manipulatives.

Multilingual Word Collections

Encourage your multilingual learners to collect vocabulary in all their languages, as a way to harness and develop their full linguistic competencies. (Ehrenworth et al., 2025; Garcia et al., 2017). Here, students investigate cognates, both so they can extend their word recognition across languages, and so they become more conscious of the crossover of language. This kind of cognitive flexibility will enrich their word consciousness in all languages.

Morphology Displays

Even very young readers benefit from learning morphology, so that they are better able to decipher or approximate the meaning of many words (Sedita, 2018; Shanahan, 2018). English is a language with many origins, and only about half of English words have their origins in Greek and Latin roots and affixes (prefixes and suffixes). But half is a lot, and once you know that re generally means back or again, that knowledge can help you figure out the probable meaning of words like rewrite, reread, redo, reexamine, rebuild, reorganize, and so on. Making room on your walls to display your morphology investigations makes it more likely that students can add to these displays, turn to them as they read and write, and generally incorporate them into their ongoing reading and writing work.

Innovating, Piloting, Planning

I hope some of these ideas have struck a chord with you. You can find full discussions and lessons at Vocabulary Connections: A Structured Approach to Deepening Students’ Expressive and Academic Language. The beautiful thing about embracing vocabulary instruction is that students love it, they respond immediately, and you’ll notice how their written and verbal expression becomes more nuanced. You’ll also see an effect on their reading. As children read, they acquire more sophisticated vocabulary, and as they acquire vocabulary, complex texts become more comprehensible. You don’t have to be perfect at this work to be terrific at it – just make an effort to add vocabulary acquisition and exploration into the studies your students will naturally engage in, and listen proudly as students talk about the cumulus clouds outside your window, how malicious the villain in their story is, and how voracious they are before lunch!

Please visit www.vocabularyconnections.org, to access additional resources.

All images from Vocabulary Connections by Mary Ehrenworth. Taylor & Francis Group. © 2025. Thank you to Jennifer Zanghi for her beautiful word charts and illustrations, and to generous teachers for sharing their classroom word walls.

References

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., Kucan, L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed). The Guilford Press.

Cabell, S. (2020). Choosing and Using Complex Text: Every Student, Every Day. Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. https://www.doe.mass.edu/massliteracy/literacy-block/complex-text/choosing-using.html

Cenoz, J., Leonet, O., & Gorter, D. (2022). Developing cognate awareness through pedagogical translanguaging. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(8), 2759–2773. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1961675

Cunningham, K. E., Burkins, J. M., & Yates, K. (2023). Shifting the balance: 6 ways to bring the science of reading into the upper elementary classroom. Stenhouse Publishers.

Duke, N. K., Ward, A. E., & Pearson, P. D. (2021). The Science of Reading Comprehension Instruction. The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1993

Ehrenworth, M. (2025). Vocabulary connections: A structured approach to deepening students’ academic and expressive language. Routledge.

Ehrenworth, Mary, Gould, Lauren, & Roman, Alexandra. (2025). Joyful Vocabulary Acquisition: Pedagogies for Developing Children’s Literary Vocabulary (and Analysis of Characters in Narratives). In Multiliteracies, Multimodality and Learning by (Inclusive) Design in Second Language Teacher Education (Agustín Reyes-Torres, María Estela Brisk, and Manel Lacorte). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

García, O., Ibarra Johnson, S., Seltzer, K., & Valdés, G. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Caslon.

Hiebert, E. H. (2011). Growing Capacity with Literary Vocabulary: The Megaclusters Framework. American Reading Forum Yearbook, 31.

Hiebert, E. H. (with Teachers College Press). (2020). Teaching words and how they work: Small changes for big vocabulary results. Teachers College Press.

Shanahan, T. (2023, June 3). How I teach students to use context in vocabulary learning |. Shanahan on Literacy. https://www.readingrockets.org/blogs/shanahan-on-literacy/how-i-teach-students-use-context-vocabulary-learning