7 Powerful Teaching Moves that Engage Teens and Elevate Their Writing

Reading time

Date posted

By Coley Conter, Mary Ehrenworth, and Lauren Gould, the authors of A High School English Teacher’s Guide To Writing Memoir and A High School English Teacher’s Guide To Writing Literary Analysis.

Most high school teachers see themselves as contentexperts, which means their curriculum development is closely tied to their teacher-identities. That twining of content and identity is what can make high school classrooms so intimate and beautiful.

As we researched our new books A High School English Teacher’s Guide To Writing Memoir and A High School English Teacher’s Guide To Writing Literary Analysis, working in many high school classrooms, learning alongside highly effective teachers and coaches, we saw this beauty first-hand. This work nudged us toward some high leverage instructional moves that will help any high school teacher who teaches writing.

Below we break down the importance of a few of these impactful practices.

1. Modeling Your Own Writing Process

As students move up the grade levels, the writing tasks they face become increasingly complex–and simultaneously, fewer teachers demonstrate how to tackle these challenges. Our most high-leverage pedagogy, then, is demonstration. When you show your writing to students, you have a few choices. You could show a small chunk of it while explaining your process as a writer. You could lead an inquiry and invite students to notice and name the moves and decisions you made as a writer. Above all, it’s best to write or think about your writing in front of students in real time. Writing in front of your students allows them to see you grapple with the same process they will encounter. Sometimes when we show young writers only our polished pieces, the writing can seem unattainable. You can also invite kids to write along with you, asking them to try out what the dialogue in a particular part might sound like or asking them to help you analyze a quote.

2. Offering Responsive Feedback and Coaching

Feedback can build confidence, it highlights what writers are doing well, and it coaches them in next steps. We’ve found that when you’re planning a writing lesson, it’s also helpful to craft some prompts for conferring, ones you think will help you coach individual writers or partnerships. Often it’s worth it to think about the predictable ways that some students might benefit from a little support, while others may be ready to extend the work of the lesson. For example, here you see suggestions from A High School Teacher’s Guide to Writing Memoir for supporting kids once you’ve taught a lesson on crafting compelling dialogue:

Prompots to Coach Students and Partnerships:

Sometimes you realize that you already have a lot of dialogue, and then the question you can ask yourself is: Where can my dialogue be more powerful?

If you don’t have any dialogue in your story, ask yourself if dialogue might help develop the perspective of other characters.

Adding tone of voice and body language has a surprising effect—it often adds to tension in a story. You can think about how it either can contrast or reinforce what is said.

3. Leveraging Writing Partnerships

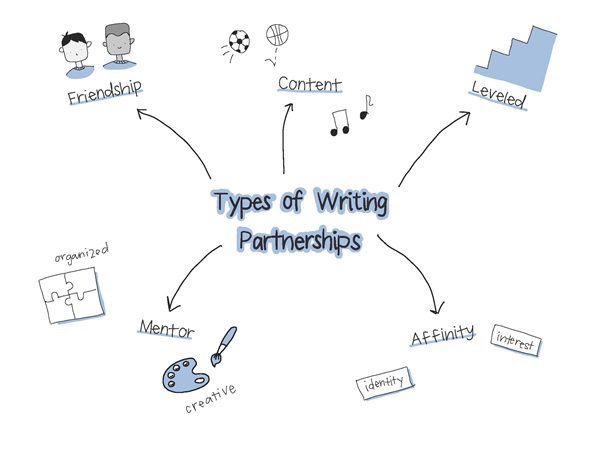

Of all the work that teens do in school, writing is where they take the most risks, and need continual support in feedback. That’s where writing partnerships come in. We’ve found that it’s helpful to start with friendship partnerships. Teens are going to do braver, better work in the company of peers whom they trust. You might also consider partnerships based on proficiency, on writing goals, on genre or content. These learning alliances capture the sense of students as interdependent beings, joined in a learning coalition. The main consideration is that once writers begin to share their stories with a partner, they should talk to that same partner across the writing process. Across our guides, we tuck in suggestions for how and when to use writing partnerships, often suggesting that you offer feedback to partnerships, not just one student at a time.

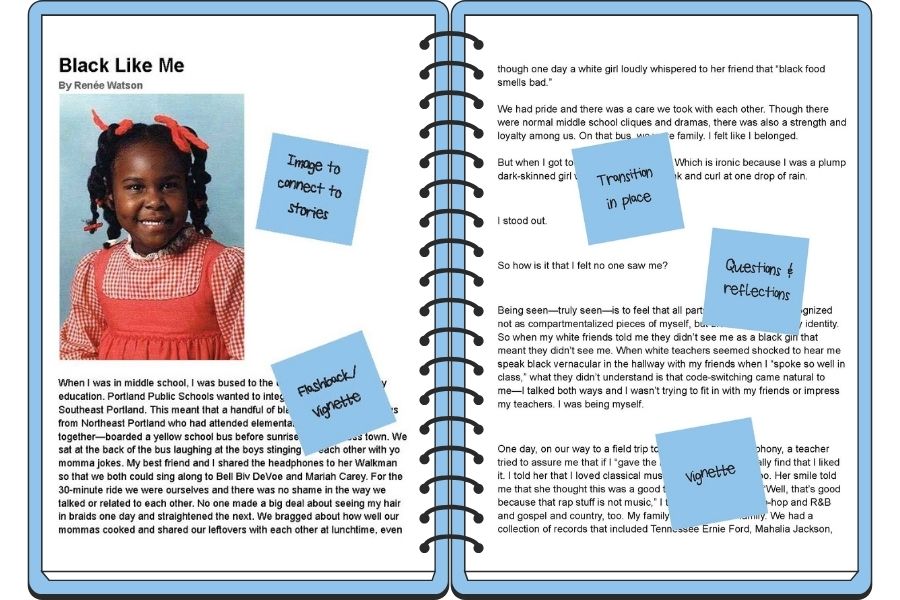

6. Sharing Engaging Mentor Texts:

You’ll want to emphasize how writers turn to mentor texts across the writing process, so that your writers, no matter what genre they are working on, or where they are in the writing process, know they can seek mentor texts to help them raise the level of their writing. Across both guides, you’ll see that we include mentor text lessons to help students get to know the genre, to study how structures support meaning, to explore the kinds literary craft published writers use to enhance their work, and to see examples of the different modalities they publish in.

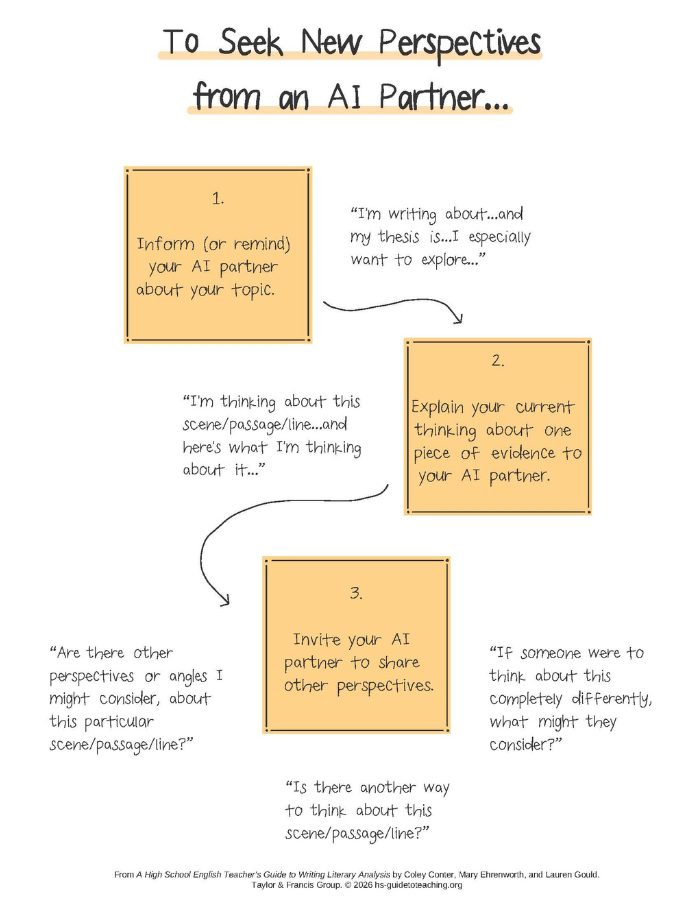

7. Leaning into AI in the Classroom

As we wrote these books, AI was quickly becoming a looming presence that all high school English teachers were forced to reckon with. We knew we couldn’t possibly create a guidebook that didn’t address this. So, instead of running away from AI, we embraced it. Across each of our guides, you’ll find several lessons that teach students how to responsibly use AI across the writing process. AI can give remarkably expert, insightful feedback to students, in a kind and affirming tone that young writers need. And teens need to learn why not to turn the work of drafting over to AI—both for ethical reasons and also so that AI helps them become more powerful writers, rather than replacing them.

Check out the Books to Learn More

If you’re ready to know more, check out the first two guides in our collection, A High School Teacher’s Guide to Writing Memoir and A High School English Teacher’s Guide to Writing Literary Analysis. As we built these collections of instructional tools, we started with the premise that we wanted to engage both students and teachers. These books are made up of lessons that work across the writing process. Our hope is that teachers see each lesson as an invitation to experiment, to add their own style, and to meet the needs of the kids in front of them. Teachers might create curriculum from these resources, or add to their existing curriculum.

Tucked inside of each lesson, in addition to the charts, mentor texts, and student writing samples, are instructional practices we know to be valuable for student engagement and student learning. Across our guides, teachers will find pedagogy that celebrates modeling writing in front of students, offering responsive feedback, leveraging writing partnerships, and sharing engaging mentor texts, to name just a few.

Ultimately, the A High School English Teacher’s Guide To collection is less about the “right” way to teach writing and more about honoring the complexity of the work teachers already do. Writing instruction is deeply human, and the practices highlighted here are powerful because they keep students and teachers at the center of the process. Our ultimate goal is for writing instruction to spark curiosity, risk-taking, and joy.

A High School English Teacher’s Guide to Writing Literary Analysis

This ready-to-use guide invites teachers to reimagine literary analysis as something intimate, authentic, intellectual, and joyful with over 50 flexible lessons, tools, charts, and mentor texts to make literary interpretation both rigorous and relevant.

A High School English Teacher’s Guide to Writing Memoir

Help your students see themselves through the power of story! This guidebook walks teachers through each stage of memoir writing, from generating story ideas and experimenting with structure to revising with intention and experimenting with conventions.